A Study of Our Shiitake Powder Highlighted from a “Food is Medicine” Perspective

Tag: #Vitamin D #Food is Medicine #gut microbiota #serotonin #Wnt/β-catenin #obesity #metabolic health #Western diet #animal study #research summary

Table of Contents

How Shiitake Powder Keeps the Gut Healthy and Helps Curb Weight Gain

1. A new paper using our forest-grown shiitake powder

A research group at the University of Massachusetts Amherst has published a paper in The Journal of Nutrition titled:

They used our forest-grown shiitake powder (SUGIMOTO Co.) in a mouse study and looked at what happens in the gut when shiitake powder is added to a Western-style high-fat diet.

In short, they found that adding shiitake powder:

-

made it harder for mice to gain weight and store fat

-

improved the balance of gut bacteria

-

calmed down two important internal signaling systems in the gut

-

the serotonin system and

-

the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

-

All of this suggested that shiitake powder helped keep the gut in a healthier state, even under a high-fat diet.

Forest-grown Shiitake powder <= Click

2. Why this paper matters for “Food is Medicine”

In the United States, the idea of “Food is Medicine (FIM)” has rapidly gained attention in recent years.

Instead of relying only on drugs and surgery, the FIM movement aims to officially build food-based interventions into the medical system to prevent and manage chronic diseases.

-

In 2022, the White House held the Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health for the first time in about 50 years and announced a national strategy to reduce hunger and diet-related chronic disease by 2030.

-

One of the pillars of that strategy is to expand programs where doctors and healthcare systems “prescribe” healthy foods such as produce, medically tailored meals, and grocery boxes.

This new shiitake study appears in a special issue of The Journal of Nutrition focused on exactly this Food is Medicine theme.

In other words, our shiitake powder was chosen as a food worth studying from a “Food is Medicine” point of view.

Of course, eating shiitake does not cure disease, and this is still basic research in mice.

But it is very meaningful that a traditional Japanese food was examined seriously as a potential “medical-grade” food ingredient.

3. What makes this study innovative?

This paper is innovative in at least three ways.

1) It uses shiitake powder as a food, not just an extract

Many mushroom studies use only isolated extracts from shiitake, such as purified β-glucan.

In this study, however, the researchers used a commercially available, forest-grown shiitake powder (SUGIMOTO Co.) and simply mixed 5% of it into a Western-style high-fat diet for mice.

In other words, they asked a very practical question:

“If we just add shiitake powder as a food, not as a supplement, to an unhealthy high-fat diet, how much can we improve what is happening inside the body?”

This “whole-food approach” is one of the key new points of the study.

2) “Japanese traditional food × Western diet” is a combination with global relevance

Another important point is that the base diet in this research is not Japanese food, but a Western-style high-fat diet that is common in the U.S. and many other countries. This kind of diet is:

-

high in fat and energy

-

low in vegetables and dietary fiber

-

linked to a higher risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

The researchers did not try to change this “problematic” diet into a perfect traditional Japanese diet.

Instead, they kept the Western-style diet as it is and simply added Japanese forest-grown shiitake powder as a food ingredient, then carefully observed what happened in the gut.

This design makes the findings easy to imagine in real life:

“Could adding Japanese shiitake powder to everyday Western-style meals make them a little healthier from the inside?”

If such an approach works, it has the potential to improve eating patterns not only in Japan but all over the world.

3) A very simple, realistic question: “What happens in the gut if we just add shiitake powder?”

When 5% shiitake powder was added to the high-fat diet, after 12 weeks:

-

the average body weight of the high-fat + shiitake group was about 10% lower than the high-fat only group

-

the amount of body fat was roughly 30% lower in the shiitake group than in the high-fat only group

(These percentages are approximate values, read by eye from the bar graphs in Figure 1. Mouse study.)

In the paper, the authors explain that their goal was to see whether shiitake powder could be used as a Food-Is-Medicine strategy to improve the “quality” of a Western-style high-fat diet, rather than to completely change the diet itself. They focused especially on the combined effects on:

-

the gut microbiota

-

the gut serotonergic (serotonin) system

-

and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

and how these three systems interact to influence gut health under a high-fat diet.

Note: This study was conducted in mice.

The results do not directly prove effects in humans, and future clinical studies will be needed to evaluate human health benefits.

4. About the research team

This project was carried out at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and supported by a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) grant of about 300,000 USD to study how incorporating mushrooms into a Western-style diet might improve gut health and reduce the risks associated with high-fat eating patterns.

The principal investigator, Professor Zhenhua Liu, is a leading researcher in nutrition:

-

He served as Chair of ASN’s Cancer and Diet Section in 2022–2023, after previously serving as chair-elect.

-

In 2025, he was selected as an Excellence in Nutrition Fellow (FASN) of ASN, which recognizes outstanding contributions to nutrition science.

In other words, this shiitake powder study was:

-

funded by a major U.S. federal agency (USDA), and

-

led by a senior nutrition scientist who is highly respected in the American Society for Nutrition.

This background also adds weight to the decision to feature our forest-grown shiitake powder in a Food-Is-Medicine–themed special issue of The Journal of Nutrition.

The figures from the original article shown in this post are used with the kind permission of Dr. Liu and the research team. Copyright in these figures belongs exclusively to Dr. Liu and the co-authors. Their use is authorized only for viewing on this website, and any reproduction, copying, modification, or secondary use of the images (including use in printed materials, presentations, social media, or other websites) is strictly prohibited without prior permission from the copyright holders.

You are, of course, very welcome to share the URL of this page.

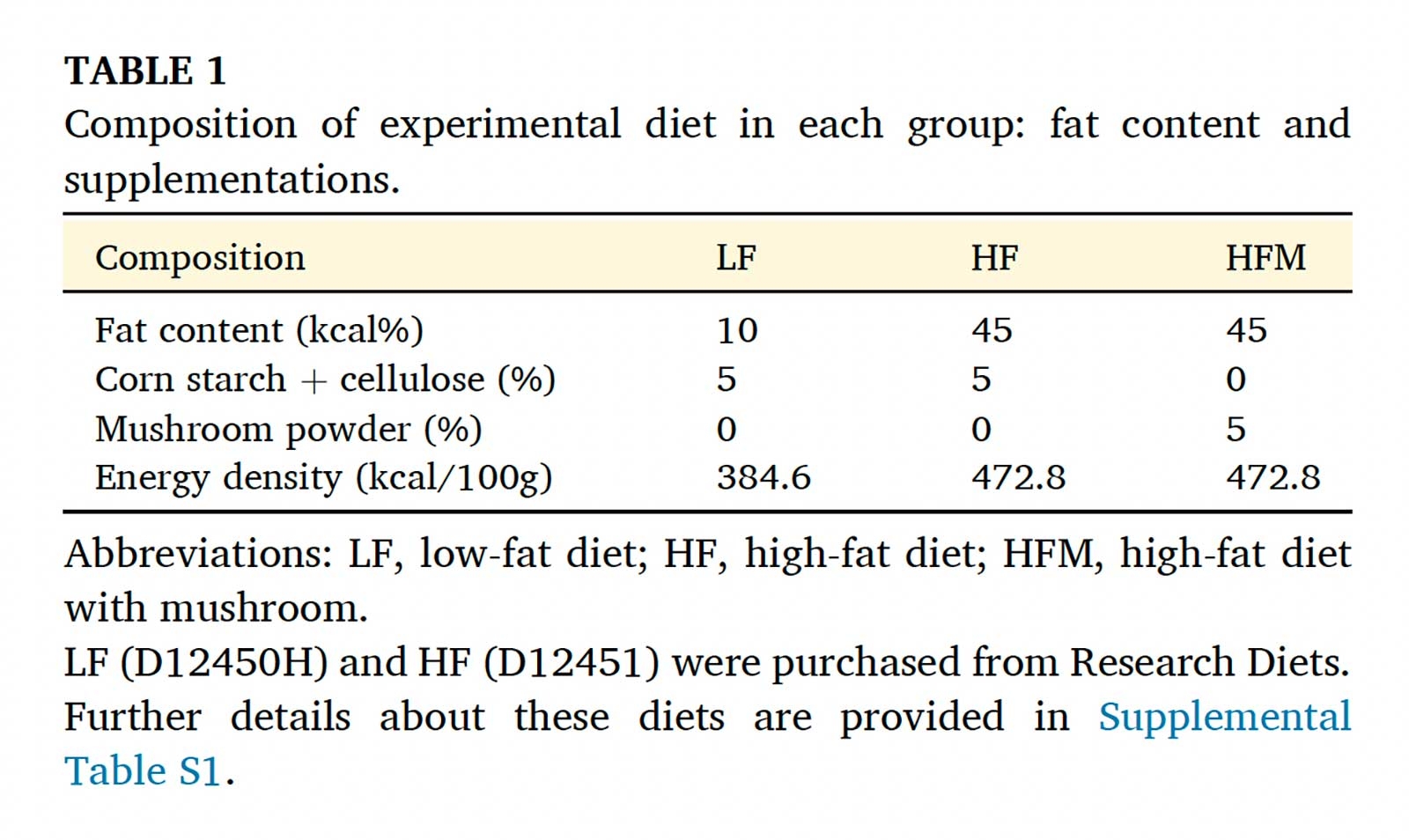

5. Study design – three diets for 12 weeks (Table 1, Figure 1A)

In Table 1 and Figure 1A, the researchers show how the diets were set up.

Male C57BL/6 mice were divided into three groups (12 mice per group) and fed for 12 weeks:

-

LF (Low-fat diet)

-

10% of calories from fat

-

plus 5% cornstarch and cellulose

-

-

HF (High-fat diet)

-

45% of calories from fat

-

plus 5% cornstarch and cellulose

-

-

HFM (High-fat + Mushroom)

-

the same high-fat diet (45% of calories from fat)

-

but the 5% cornstarch + cellulose was replaced with 5% shiitake mushroom powder (SUGIMOTO Co.)

-

So HF and HFM have the same calories and the same fat ratio.

The only difference is that in HFM, part of the diet is replaced by shiitake powder instead of cornstarch + cellulose.

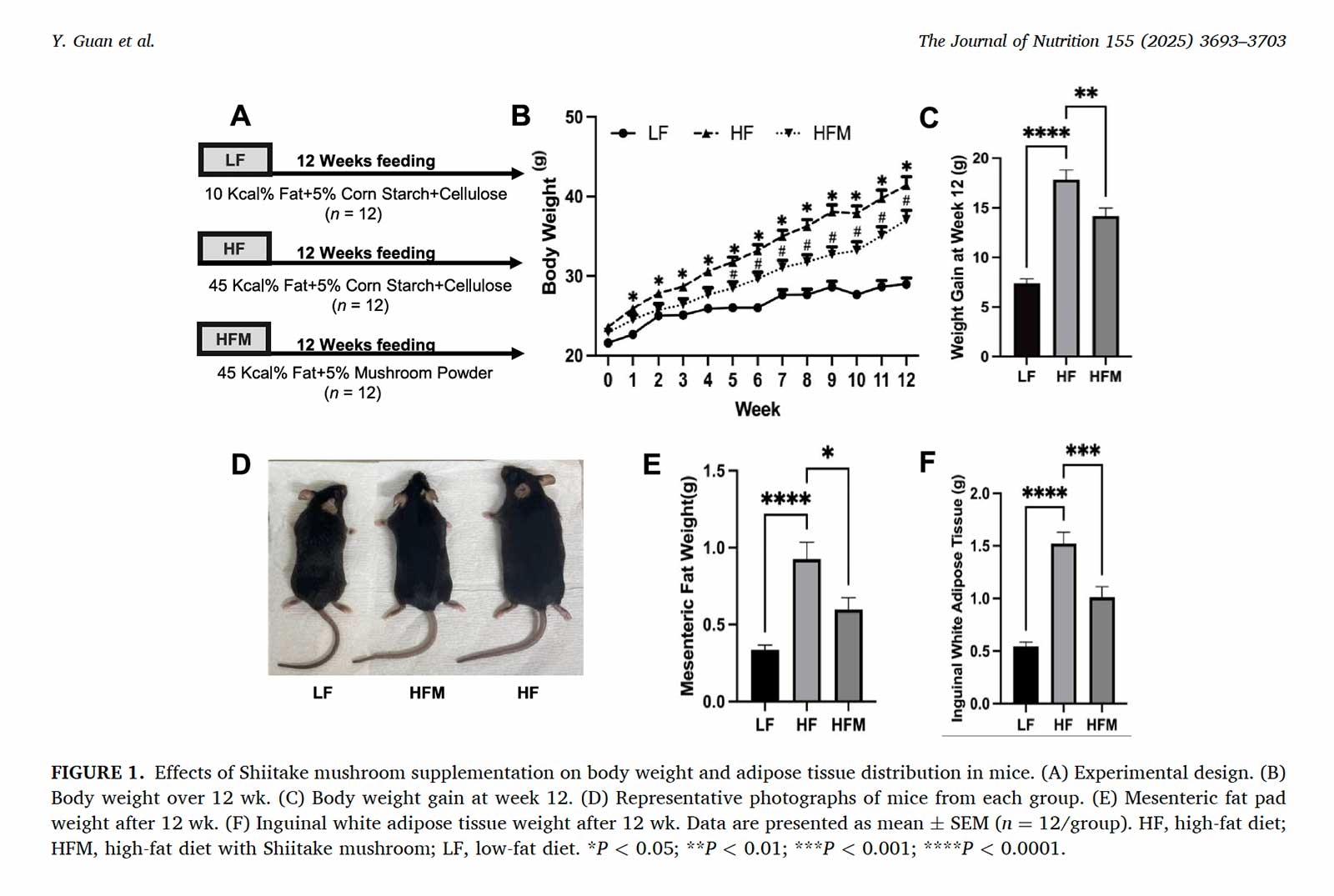

In Figure 1A, you can see a simple timeline:

-

three groups of mice

-

12 weeks of feeding with these three diets

-

and then measurements such as body weight, fat mass, blood tests, and tissue samples at the end.

6. What happened to body weight and fat? (Figure 1B–F)

Figure 1B–F show what happened to the mice’s body weight and body fat.

Figure 1B – Body weight over 12 weeks

-

Figure 1B is a line graph showing body weight every week.

-

The lowest line is the LF group (low-fat diet) – their weight increases only slowly.

-

The two upper lines are HF and HFM (high-fat diets), and both gain more weight.

-

However, HFM (with shiitake) stays lighter than HF throughout the 12 weeks.

-

As time goes on, the gap between HF and HFM becomes clearer.

Figure 1C – Total weight gain after 12 weeks

-

Figure 1C is a bar graph showing how many grams of weight each group gained after 12 weeks.

-

HF gained the most weight.

-

LF gained the least.

-

HFM gained significantly less weight than HF, even though both diets were high in fat.

-

The asterisks (*) above the bars show that this difference is statistically meaningful, not just due to chance.

From Figure 1B and 1C, we can roughly read that:

-

After 12 weeks, the average body weight of the HFM group was about 10% lower than that of the HF group.

-

(This percentage is an approximate value estimated from Figure 1.)

Figure 1D – Photos of the mice

-

Figure 1D shows photos of mice from each group, seen from above.

-

You can clearly see that:

-

HF mice look the biggest and roundest.

-

HFM mice are leaner than HF.

-

LF mice look the slimmest.

-

This photo panel helps us visually grasp the differences shown in the graphs.

Figure 1E – Mesenteric fat (fat around the intestines)

-

Figure 1E is a bar graph of mesenteric fat weight – fat around the intestines inside the abdomen.

-

HF has the most mesenteric fat.

-

LF has the least.

-

HFM has significantly less mesenteric fat than HF.

-

From the graph, we can roughly estimate that mesenteric fat in HFM is about 30–40% lower than in HF.

Figure 1F – Inguinal white adipose tissue (subcutaneous fat)

-

Figure 1F is a bar graph of inguinal white adipose tissue – subcutaneous fat near the groin.

-

Again, HF is the highest, LF is the lowest, and HFM is clearly lower than HF.

-

From the bars, we can roughly estimate that this fat depot is about 40% less in HFM than in HF.

So, Figure 1B–F together show that:

-

a high-fat diet alone causes strong weight gain and fat accumulation;

-

adding 5% shiitake powder to that high-fat diet makes it harder for mice to gain weight and store fat, even though calories and fat percentage are the same.

(All percentages here are approximate values estimated from Figure 1.)

7. A quick refresher – what is the gut microbiota?

Before looking at the next figures, let’s recall what the gut microbiota is.

-

Our intestines are home to a huge community of bacteria and other microbes.

-

When this community has many different types of bacteria living in balance, the gut tends to stay healthy.

-

A high-fat, low-fiber diet can disturb this balance:

-

helpful bacteria that digest fiber decrease

-

other bacteria that like fat and bile increase

-

the mucus layer that protects the gut can become thinner

-

These changes are linked to obesity, diabetes, fatty liver disease, and intestinal inflammation.

The next figures show how the three diets affected this gut community.

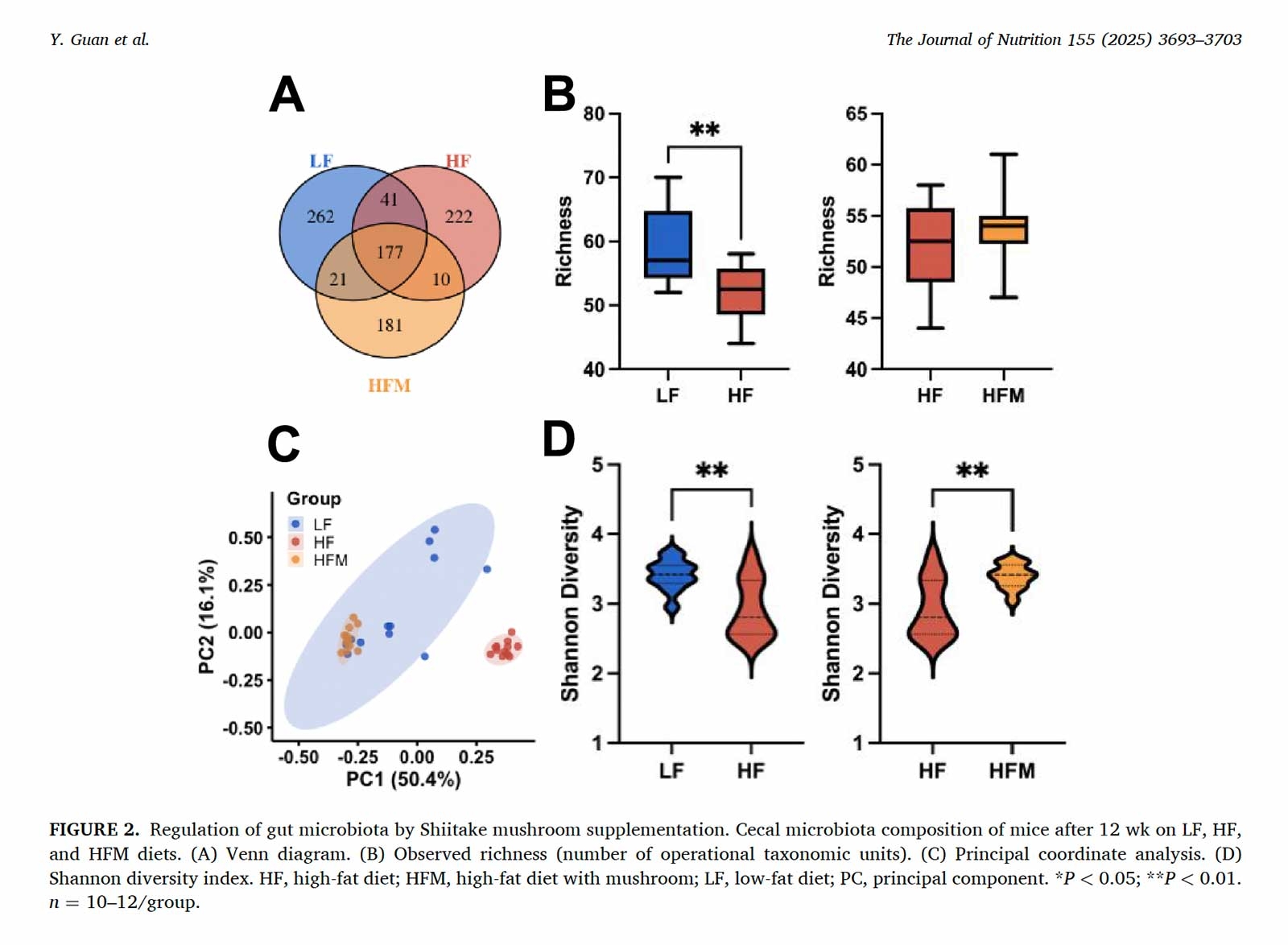

8. How did shiitake powder change gut bacteria? (Figure 2A–D)

Figure 2A–D look at the diversity and overall pattern of the gut microbiota in each group.

Figure 2A – Venn diagram of bacterial types

-

Figure 2A is a Venn diagram showing how many types of bacteria (OTUs) were found in each group.

-

Each circle represents one group (LF, HF, HFM).

-

Numbers in the non-overlapping parts show bacteria unique to that group.

-

Numbers in the overlapping parts show bacteria shared between groups.

From this, we see that each diet leads to a somewhat different set of bacteria; the membership of the gut community changes when the diet changes.

Figure 2B – Richness (number of different types)

-

Figure 2B compares richness – roughly, “how many different kinds of bacteria” there are.

-

On the left, LF vs. HF:

-

HF has lower richness than LF → a high-fat diet reduces the variety of bacteria.

-

-

On the right, HF vs. HFM:

-

HFM has significantly higher richness than HF → shiitake powder helps restore the variety of bacteria.

-

Figure 2C – Overall pattern (PCoA plot)

-

Figure 2C is a PCoA plot (principal coordinates analysis).

-

Each dot is one mouse; colors show the three groups.

-

Dots from each group cluster in different areas:

-

LF dots cluster in one region,

-

HF in another,

-

HFM in a third region.

-

This means the overall pattern of gut bacteria is clearly different among LF, HF, and HFM.

HFM is not just in between LF and HF; it has its own distinct pattern created by the addition of shiitake powder.

Figure 2D – Shannon diversity (variety + balance)

-

Figure 2D shows the Shannon diversity index, which captures both:

-

how many types of bacteria there are, and

-

how evenly they are distributed.

-

-

LF has the highest diversity.

-

HF has lower diversity → the community becomes less balanced and more dominated by certain bacteria.

-

HFM shows higher diversity than HF, with a significant difference, meaning shiitake powder helps bring back a more balanced, varied gut microbiota.

Overall, Figure 2A–D tell us:

A high-fat diet alone makes the gut bacterial community poorer and less balanced,

but adding shiitake powder helps bring back more types of bacteria and a healthier balance.

9. Which bacteria went up or down? (Figure 3A–D, Figure 4A–D)

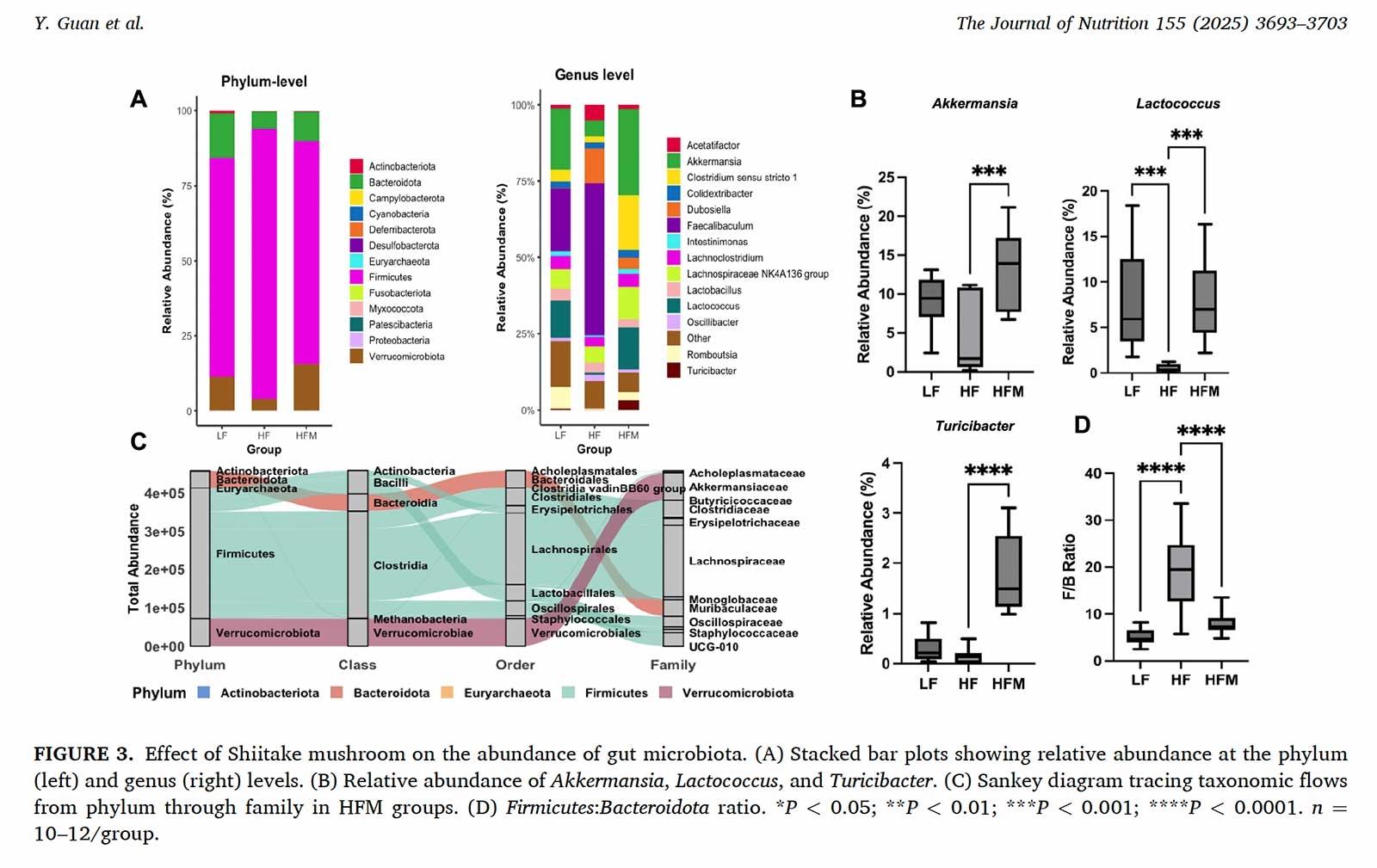

Next, Figure 3A–D and Figure 4A–D zoom in on which bacteria changed.

Figure 3A – Big groups (phyla) in each diet

-

Figure 3A shows stacked bar charts of gut bacteria at the phylum level (very big groups).

-

Each bar is one mouse; colors show different phyla such as Firmicutes and Bacteroidota.

-

In HF, the bars have a large pink portion (Firmicutes) and relatively less Bacteroidota.

-

In HFM, this imbalance is less extreme, and the pattern moves closer to LF.

This is related to the Firmicutes/Bacteroidota (F/B) ratio, which is often higher in obesity.

Figure 3B – Important genera (Akkermansia, Lactococcus, Turicibacter, etc.)

-

Figure 3B picks out specific genera (smaller groups), such as:

-

Akkermansia – helps maintain the mucus layer and is associated with better metabolic health

-

Lactococcus – a lactic acid bacterium

-

Turicibacter – may be linked to short-chain fatty acid production and gut immunity

-

-

In the results:

-

HF often reduces Akkermansia and Turicibacter.

-

HFM increases these beneficial bacteria, often above LF levels.

-

Some bacteria that grow too much on HF are brought back down in HFM.

-

Figure 3C – Family tree in HFM (Sankey diagram)

-

Figure 3C is a Sankey diagram that follows the “family tree” of bacteria in HFM:

-

from phylum → class → order → family and so on.

-

-

The thickness of each band shows how many bacteria belong to that branch.

-

You can see that branches linked with short-chain fatty acid producers and mucus-related bacteria stand out in HFM.

You don’t need to read every label; the main idea is that shiitake powder supports whole families of helpful bacteria.

Figure 3D – Firmicutes/Bacteroidota (F/B) ratio

-

Figure 3D shows the F/B ratio directly.

-

LF has a lower ratio.

-

HF has a much higher ratio (Firmicutes dominate).

-

HFM lowers the ratio again, closer to LF, with strong statistical significance.

A high F/B ratio has been linked to obesity and metabolic problems, so this shift is considered positive.

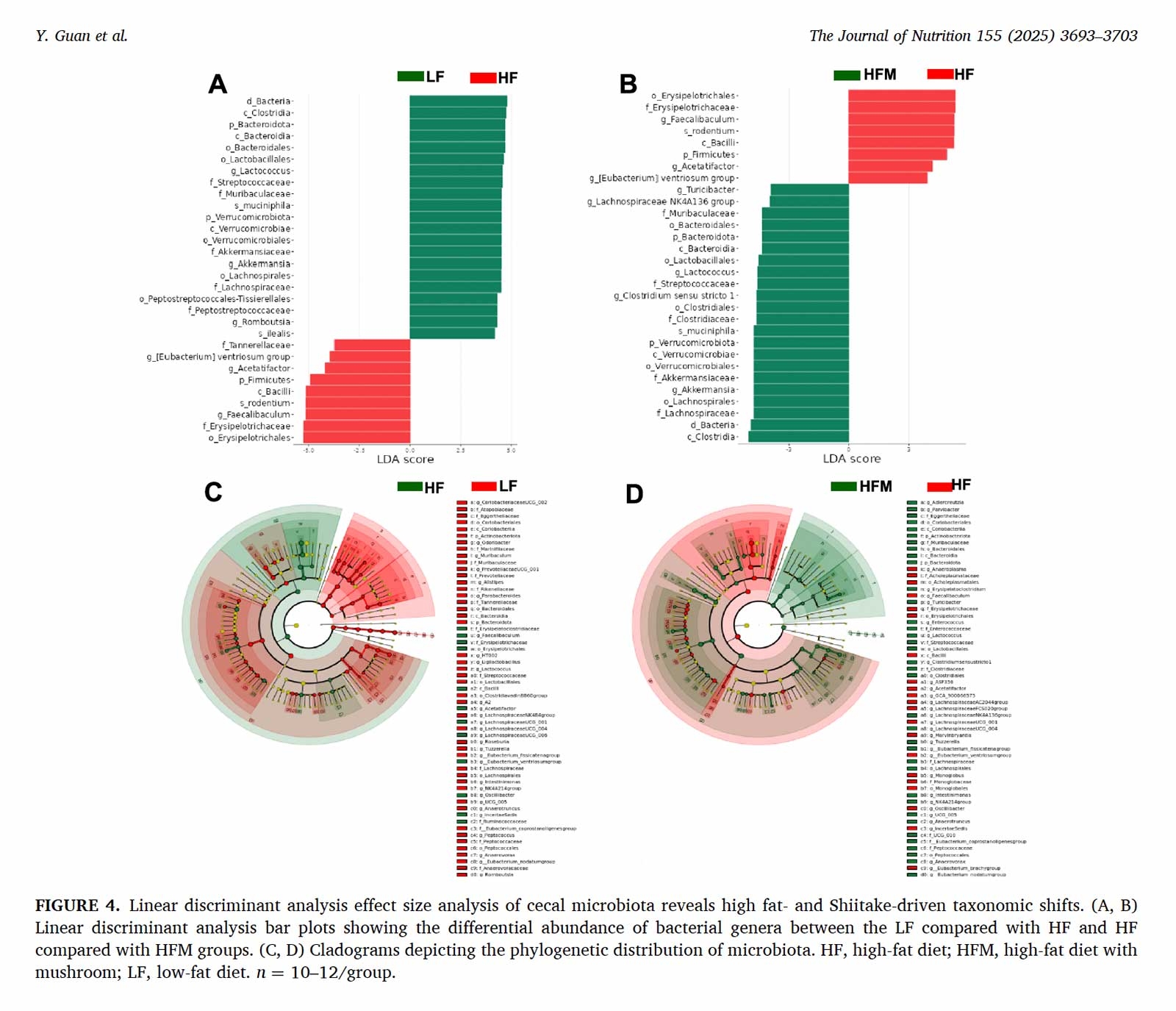

Figure 4A – “LF-like” vs. “HF-like” bacteria (LF vs HF)

-

Figure 4A uses a method called LEfSe to show which bacteria are characteristic of LF or HF.

-

Green bars: bacteria that are more abundant in LF than in HF.

-

Red bars: bacteria that are more abundant in HF than in LF.

-

Many helpful bacteria (such as some Bacteroidota and Verrucomicrobiota, including Akkermansia) appear on the LF side.

-

Several bacteria that tend to increase under high-fat conditions appear on the HF side.

You can read this as:

“These are the bacteria that make LF look like LF, and these are the ones that make HF look like HF.”

Figure 4B – “HFM-like” vs. “HF-like” bacteria (HFM vs HF)

-

Figure 4B does the same comparison, but this time HFM vs HF.

-

Green bars: bacteria that are more abundant in HFM than in HF.

-

Red bars: bacteria that are more abundant in HF than in HFM.

-

Here, Akkermansia, Turicibacter, and some other beneficial groups are clearly enriched in HFM.

-

High-fat–associated groups stay on the HF (red) side.

So, in simple terms:

When shiitake powder is added to the high-fat diet, the gut becomes less HF-like and more LF-like in terms of which bacteria dominate.

Figure 4C and 4D – Family trees colored by diet

-

Figure 4C shows a phylogenetic tree (family tree) of bacteria, colored to highlight LF vs HF differences.

-

Figure 4D shows a similar tree for HFM vs HF.

-

Green branches indicate groups associated with LF or HFM.

-

Red branches indicate groups associated with HF.

Even without reading every name, you can see:

-

In Figure 4C, many branches are green on the LF side.

-

In Figure 4D, many branches are green for HFM, showing that many different lineages of bacteria are more active when shiitake powder is present, compared with HF alone.

Together, Figure 3 and Figure 4 show that:

-

A high-fat diet strongly reshapes the gut microbiota in an undesirable direction.

-

Adding shiitake powder shifts the community toward a richer, more balanced, and more “LF-like” composition, with more good-leaning bacteria such as Akkermansia and Turicibacter.

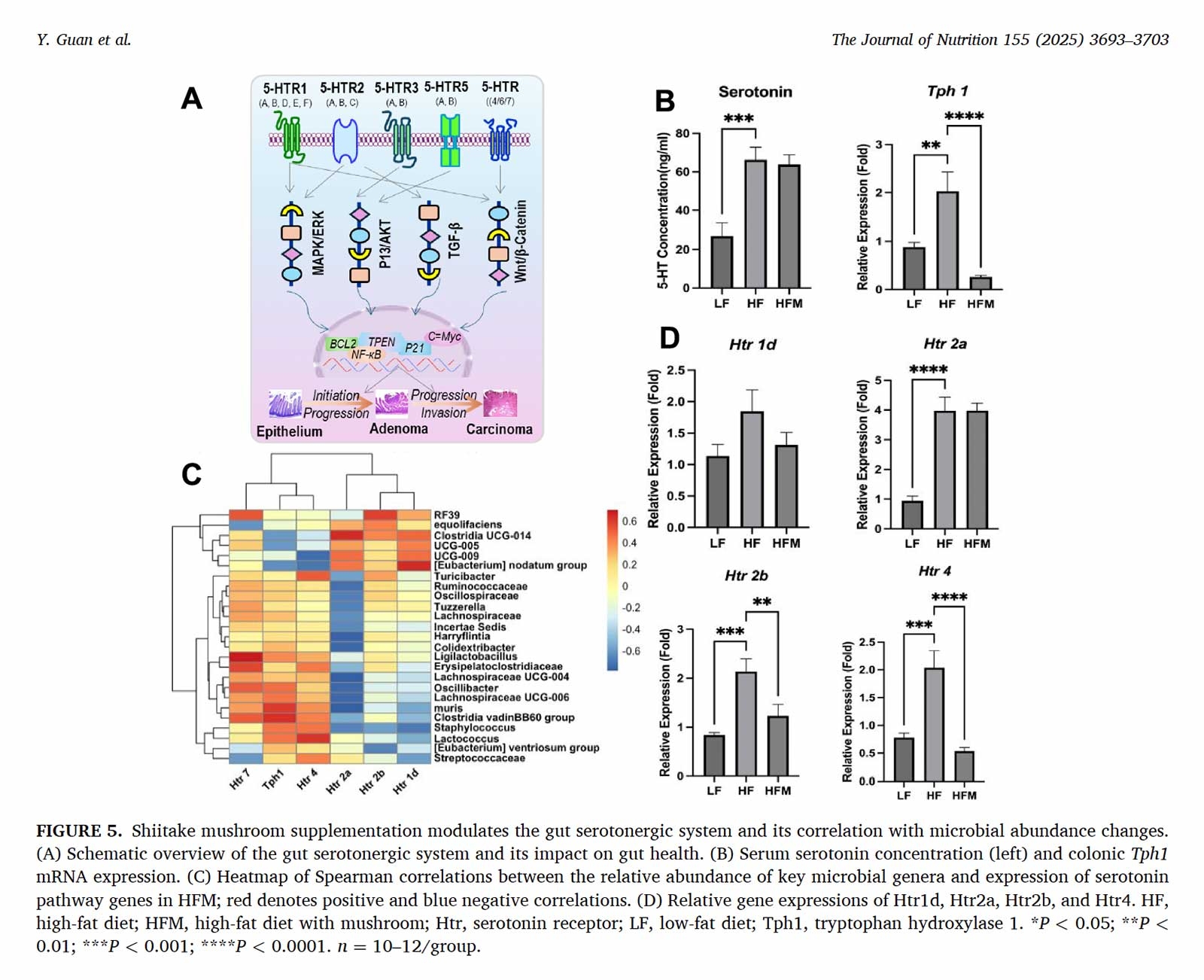

10. Serotonin in the gut – more than just a “happy hormone” (background, Figure 5A)

Figure 5A is a diagram showing how the gut serotonin system works.

-

Serotonin (often called a “happy hormone” in the brain) is mostly produced in the gut.

-

It is made by an enzyme called Tph1 in special gut cells.

-

Serotonin then binds to receptors (Htr1–Htr4) on gut cells:

-

controlling gut movement

-

affecting fluid secretion

-

influencing gut sensation and even cell growth

-

Figure 5A also shows that if serotonin signaling is too strong for too long,

it can send “grow, grow, grow” signals through pathways like Wnt/β-catenin,

which may contribute to abnormal cell growth or tumors.

So, this figure explains why the researchers cared about serotonin in this study.

11. How did shiitake powder affect the gut serotonin system? (Figure 5B–D)

Figure 5B–D show what happened to the serotonin system in each group.

Figure 5B – Serotonin level and Tph1 expression

-

The left part of Figure 5B shows serum serotonin levels.

-

HF tends to have higher serotonin than LF.

-

HFM shows a tendency to bring serotonin down compared with HF.

-

-

The right part shows expression of Tph1, the enzyme that makes serotonin in the gut.

-

HF clearly increases Tph1 expression.

-

HFM clearly reduces Tph1, back towards LF levels.

-

This suggests that a high-fat diet makes the gut over-produce serotonin,

and shiitake powder helps calm this down.

Figure 5C – Correlation heatmap (bacteria vs serotonin-related genes)

-

Figure 5C is a heatmap showing correlations between:

-

specific bacteria (rows) and

-

serotonin-related genes (columns, including Tph1 and Htr receptors).

-

-

Red squares show positive correlations (both go up together).

-

Blue squares show negative correlations (one goes up when the other goes down).

In the paper, the authors note that:

-

bacteria that grew with shiitake powder (such as Akkermansia and Turicibacter)

are associated with a more normal expression pattern of serotonin-related genes.

You don’t need to read every cell of the heatmap; the key message is:

Changes in gut bacteria and changes in the serotonin system are linked.

Figure 5D – Serotonin receptors (Htr1d, Htr2a, Htr2b, Htr4)

-

Figure 5D contains four bar graphs, one for each serotonin receptor in the gut.

-

In the HF group:

-

all four receptors are up-regulated → the gut cells are too sensitive to serotonin.

-

-

In the HFM group:

-

receptor expression is reduced back towards LF levels.

-

Putting Figure 5B–D together:

A high-fat diet pushes the gut serotonin system into an overactive state.

Adding shiitake powder helps reduce serotonin production (Tph1),

and brings receptor levels back down, so the overall serotonin signal becomes more balanced.

12. What is the Wnt/β-catenin pathway? (Figure 6A)

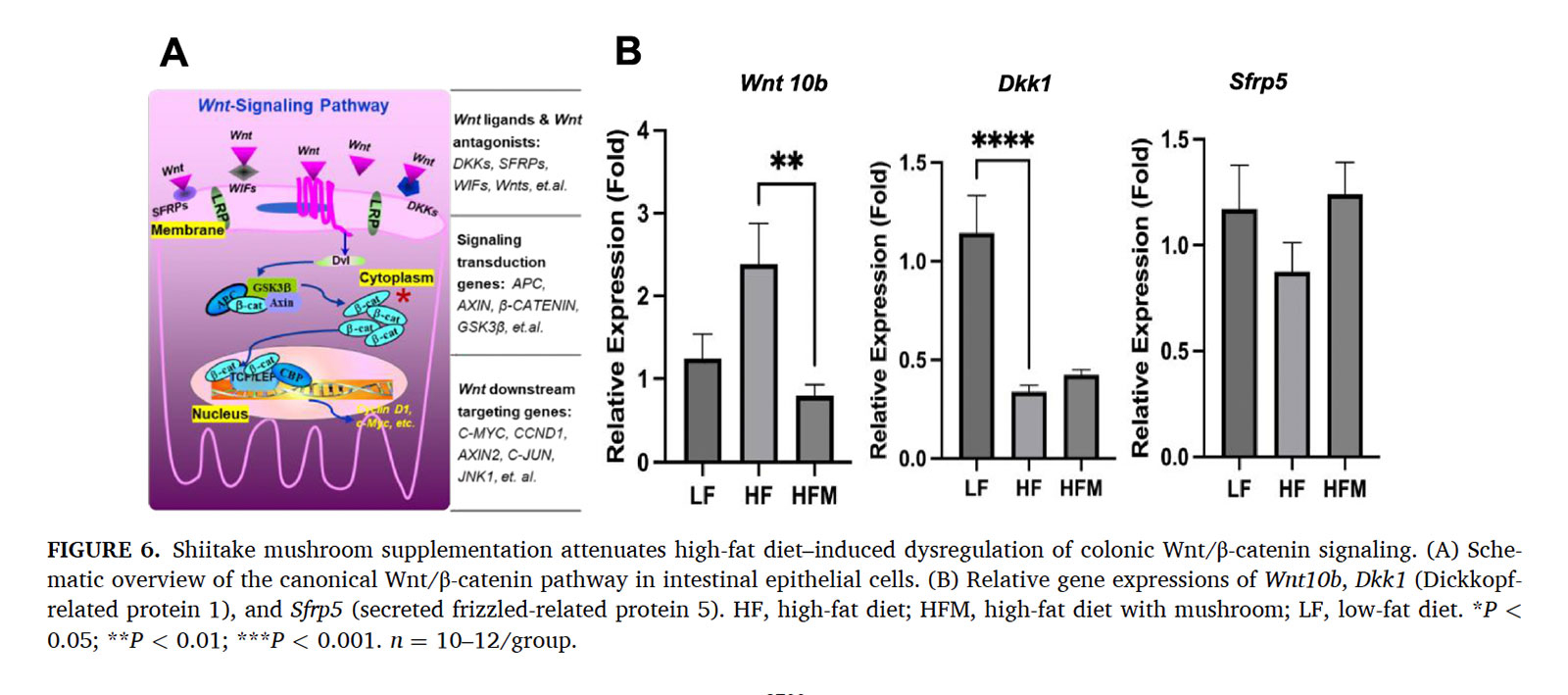

Figure 6A is another diagram, this time of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

-

Wnt is a “grow” signal that binds to receptors (Frizzled and LRP) on the cell surface.

-

When Wnt signaling is strong:

-

a protein called β-catenin builds up inside the cell,

-

moves into the nucleus, and

-

turns on genes like c-Myc and Cyclin D1 that tell cells to divide.

-

-

Dkk1 and Sfrp5 act like brakes, stopping Wnt from becoming too strong.

This pathway is important for normal tissue renewal,

but if the accelerator is pressed too hard and the brakes fail,

it can contribute to tumor development.

13. Shiitake powder calmed this growth signal (Figure 6B, Figure 7A–B)

Figure 6B – Accelerator and brakes (Wnt10b, Dkk1, Sfrp5)

Figure 6B shows expression of three key genes:

-

Wnt10b – an “accelerator” for the Wnt pathway

-

Dkk1 – a “brake”

-

Sfrp5 – another “brake”

The pattern is:

-

HF group:

-

Wnt10b goes up (accelerator pressed).

-

Dkk1 and Sfrp5 go down (brakes weakened).

-

-

HFM group:

-

Wnt10b comes back down towards LF levels.

-

Sfrp5 goes back up to LF levels or higher.

-

Dkk1 does not fully recover.

-

So, shiitake powder reduces the overactive growth signal (Wnt10b)

and restores at least one important brake (Sfrp5).

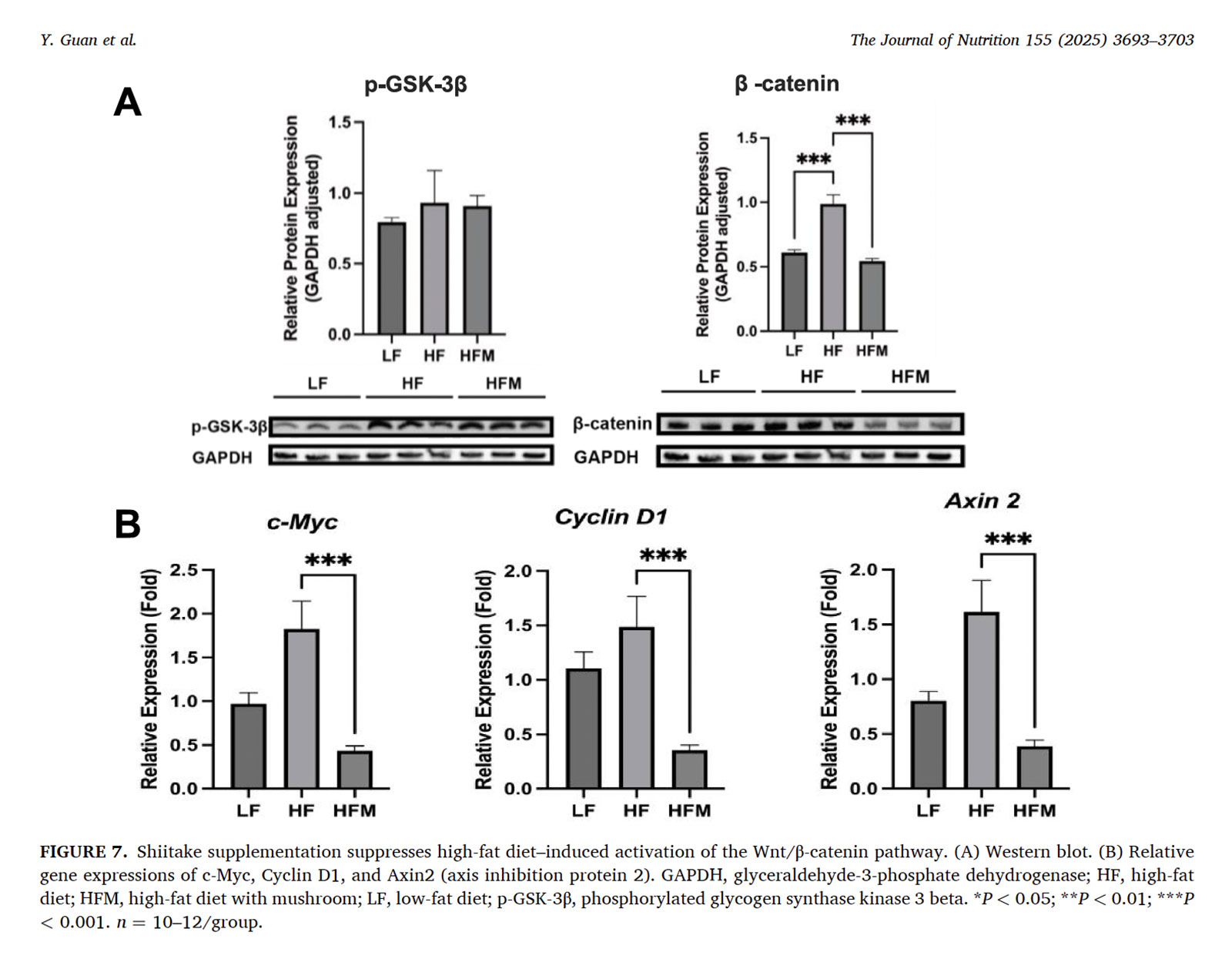

Figure 7A – β-catenin protein levels

-

Figure 7A shows the amount of β-catenin protein in colon tissue.

-

HF has much higher β-catenin than LF.

-

HFM reduces β-catenin back towards LF levels.

This means the “grow” signal inside the cells is no longer as strong when shiitake powder is present.

Figure 7B – Downstream genes (c-Myc, Cyclin D1, Axin2)

Figure 7B shows three genes that β-catenin turns on:

-

c-Myc

-

Cyclin D1

-

Axin2

-

HF group: all three are up-regulated compared with LF.

-

HFM group: all three are down-regulated again, back towards LF levels.

In simple terms:

Under a high-fat diet, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and its growth-promoting genes are overactive.

With shiitake powder, they are brought back toward a calmer, more controlled state.

This does not mean shiitake powder “prevents cancer” in humans,

but it does suggest that in mice, it helps protect the gut from runaway growth signals caused by a high-fat diet.

14. So which components of shiitake are responsible?

The paper does not pinpoint one single compound such as “this β-glucan alone did it.”

Instead, the authors discuss the effects as the combined action of multiple components present in shiitake powder, for example:

-

polysaccharides such as β-glucans

-

polyphenols

-

dietary fibers

In the discussion, they treat shiitake powder as a whole food, where many components work together to:

-

reshape the gut microbiota

-

calm the serotonin system

-

and modulate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway

leading overall to improved gut health in mice on a Western-style high-fat diet.

15. Final thoughts

To summarize this mouse study:

-

A Western-style high-fat diet disturbed the gut microbiota, pushed the serotonin system and Wnt/β-catenin pathway into an over-active state, and promoted weight and fat gain.

-

Adding 5% shiitake powder:

-

made it harder for mice to gain weight and accumulate fat

-

increased good-leaning bacteria like Akkermansia and Turicibacter, while reducing bad-leaning ones such as Acetatifactor

-

restored diversity and improved the overall balance of gut bacteria

-

helped normalize gut serotonin production and receptor expression

-

calmed the Wnt/β-catenin growth signaling pathway and its downstream genes

-

All of this happened without identifying a single “magic bullet” compound.

Instead, the researchers describe the effects as the synergy of polysaccharides, polyphenols, fibers and other components in shiitake powder acting together as a whole food.

It’s still basic research in mice, not a clinical trial in humans.

But the fact that Japanese forest-grown shiitake powder was chosen for a Food is Medicine special issue, and showed such interesting effects on gut health, is truly encouraging for us.

We will continue to follow and share new research on shiitake so that more people can enjoy it not only as a delicious ingredient, but also as a food that gently supports health from the gut.

Forest-grown Shiitake powder <= Click